A new renewal for Same Hat? I've been meaning to write for a few months now, but I found myself continuing to delay compiling all my shreds of random thoughts together until I could find time to attack it properly. I think you'll find the materials discussed in this post live up to the hype, and I'm hoping this will lead to a few more interesting posts and interviews being unearthed in the near future.

Concerned Theatre Journal (CTJ) debuted in October 1969, and was conceived of, coordinated, and translated by David. G. Goodman. In 1971, CTJ released the first issue of its second volume as a double-sized "cartoon special". The 116 page issue featured the following three stories:

- Sakura Illustrated ("Sakura Gaho") by Akasegawa Genpei [1971]

- Red Eye ("Akame") by Shirato Sampei [1969]

- The Stopcock ("Nejishiki") by Tsuge Yoshiharu [1969]

As nerds who've seen our ramshackle "Early Manga Days: Chronology" post, this predates the publication of translation of Barefoot Gen by seven years, and the short story "The Bushi" (written by Satoshi Hirota and art by Masaichi Mukaide) appearing in Star*Reach #7. Between 1969 and 1973, nine issues were released by Goodman and his collaborators totaling "nearly thirteen hundred pages of translated plays, criticism, and scholarship." It's an amazing treasure trove of politically-active, internationally-minded theater criticism and translations from an exciting time in Japanese history.

A great overview of the entire life of Concerned Theatre Japan can be found in Virtual CTJ, an essay which was written in early 2005. In this retrospective, Prof. Goodman explained their perspective:

The mentality was different, too. Much of what is said today about Japan’s historical amnesia, its failure to confront the legacy of the Asia-Pacific War, was not true of CTJ. Our contributors were mostly in their late twenties or very early thirties; and, like the first postwar generation in other countries, they were actively interrogating their parents’ generation and the aftermath of the war. The plays and articles in CTJ continue to be trenchant critiques of Japan’s wartime behavior.

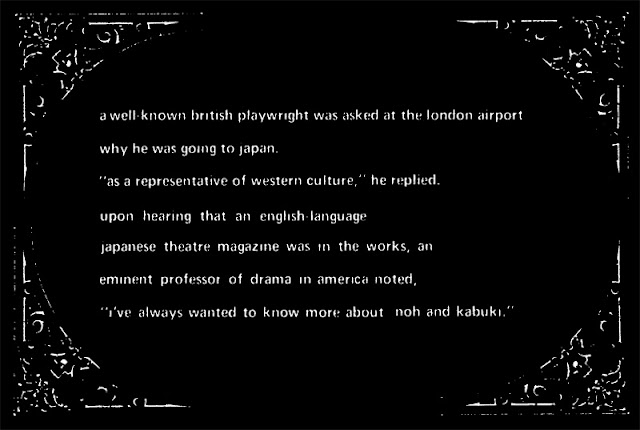

Goodman was a senior at Yale in fall of 1968, and writing about / documenting new theatre groups visiting America at the time. He explains the genesis of an English language magazine:

I learned through our correspondence of the ambitious program the June Theatre was planning in a new alliance to be called Theatre Center 68/69. The program included a plan to publish a magazine, and I proposed that an English-language sister publication be issued as well. What was needed, I argued, was a vehicle that would allow Japanese artists, writers, and scholars to participate fully in global intellectual discourse that would empower them to engage their peers around the world and be engaged by them. Tsuno responded that it was an ambitious idea, that no one knew the first thing about publishing such a magazine, and that no money was available to support it, but if I was prepared to edit it, I was welcome to do so. I decided to go ahead.

In addition to the original essays and translations of contemporary plays (and the manga issue!), TCJ features rad graphic design and interesting ads from shops and brands eager to align to themselves with the dramatic, visual, and envelope-pushing theater productions of the time:

For (much) more on the visual culture of the theater, you must check out another book edited/curated by Prof. Goodman: "ANGURA: Posters of the Japanese Avant-Garde," a book documenting the posters by Tadanori Yokoo, Hirano Koga, Shinohara Katsuyuki, and their contemporaries.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Japanese popular culture was not yet a global phenomenon. No one had ever heard of manga, much less video games and animé. The graphics we published by Akasegawa Genpei, Tsuge Yoshiharu, and Shirato Sampei were, as far as I know, the first manga ever to appear in English.I'm least familiar with Genpei Akasegawa's work, but his satirical newspaper opens up the book with a bang and firmly ties the contents that follow to the 1969 Tokyo University Protests and the aftermath of their failures and co-option.

Next up in the issue is "Red Eyes" by Shirato Sanpei, a powerful and intense period piece by one of the originators of gekiga. Sanpei is best known, in Japan and English-speaking readerships, for creating The Legend of Kamui. The manga "Red Eyes" was later adapted by Saitô Ren, and published in Concerned Theatre Japan.

Finally, on that last but not least tip, we have a translation of "Nejishiki" by Yoshiharu Tsuge -- named here as "The Stopcock"(!). This would appear 32 years later as "Screw-Style" in The Comics Journal #250. It seems silly to add much commentary to such an important and pioneering work, but it is an obvious must-read for any Same Hat fan of alternative manga-- the linchpin/shared ancestor of a lot of our favorite manga!

[ --> CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE COMPLETE PDF <-- ]

PDF hosted via the University of Michigan "Center for Japanese Studies Publications" page.

PDF hosted via the University of Michigan "Center for Japanese Studies Publications" page.

Please enjoy this incredible collection of early manga. Friend of Same Hat and manga-in-America pioneer Fred Schodt sent this thoughts in response to seeing the Concerned Theatre Japan's manga issue:

It definitely predates Gen by nearly 10 years. Whether it's the first manga translated or not, I'm not sure, because it depends on how you define manga. Short manga were being translated in Tokyo Puck at the beginning of the 20th Century, and even in Maru Maru Chinbun at the end of the 19th Century. But I've never seen these pseudo story-manga done so early. And they're all great favorites of mine. In fact, it reminded me how powerful manga were in that period. More powerful than most today, I venture, simply because of the political intensity of the period, and the radical-ness of using manga to transmit such sophisticated ideas.

[Many thanks to Paul for initially tipping me off to the existence of these online archives. Professor Goodman now teaches at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. I'm contacting him for an interview in the coming weeks.]

10 comments:

is this for real an actual post? am i on drugs, going through some sort of delusion? well if it is... is one nice trip i'm getting here!

man i have some questions i'm wondering if you could ask prof. Goodman for me,in the upcoming interview, the first one is if it was too difficult to find the support and funding to start the magazine back in 68/69.

The second one is about the comparative curve of manga back there and today, i understand they where fresh out of ww2, but how bold where the political statements and criticism that actually managed to be published in the manga media compared to our current times, to the current political figures and the state.

And the last one is, maybe if a little bit latter, Osamu tezuka is known as one of the great pushers of the commercialization and effectiveness of manga and anime as it is today, to the point that it is addressed as the god of manga, but not all of his works could be seem as highly commercial, ones examples can be MW, Adolf, and Ode to Kirihito, that unlike the others where definitively not aimed at children, so my question is really not just one, but here it goes: which effects did those works on the image of Osamu back there? would if released today still be as they used to be? or the new terms of censorship would change the thematic they work, or rather the new trends of an open global world would let him explore more bolder aspects on his works? lastly what others artist impulsed the success of manga before and alongside Osamu that time or the media may have cast on shadows, could you inform us about them?

well that is i guess, sorry if it is a little confusing to read, it is 2:20 am and English is not my main language, any way i appreciate if you could pass professor Goodman those doubts i have about the history of manga, and if it is not too much trouble i may have more ones but so far that is it, i think... thank you very much!

awesome post, i still cant believe this is not the tumblr XD

CTJ is essential to anybody with a hard on for Japanese underground culture. There is so much STUFF in every issue. The essays and translations are pure gold for a Same Hatter. It is always fun to read an alternative translation for manga such as Nejishiki, though I prefer the one in TCJ#250.

I'm wearing a pin featuring an eye doctor sign from Nejishiki for the first time today so maybe this was all meant to be a sign from the universe.

Worth the wait. Amazing manga, amazing artwork, awesome awesome awesome

@Doomroar: You are not dreaming, my friend. I just needed a little time to get re-excited about all this stuff again haha

I'll pose some of your questions if I get the chance to speak to him- though I have to tell you Goodman is more of a Theatre/politics/art specialist than a Manga specialist; I think the questions about Tezuka are more for someone like Fred Schodt not Prof. Goodman, but your question about the impact of manga as a political/artistic force is a great one.

Some of the details about the funding or the magazine is answered in the Virtual CTJ overview essay :)

Thanks for reading!!!

@zytroop: I knew that CTJ was your bread and butter, all the Terayama and exciting works (let alone simply the graphic design of each issue).

Loving your new blog, btw :)

@Jake: Glad you enjoyed it!

oh man thanks a lot! i would have that detail in mind if i ever get to talk with mister Schodt.

Not to burst any bubbles but.......The Japanese were publishing manga with English translations as early

as 1947. There was many examples, check out donguri taro. They also published our comic strips like Blondie in Japanese at the same time.

@Anonymous: Yes, that's definitely true and already noted!

As Fred says in his quote, "Whether it's the first manga translated or not, I'm not sure, because it depends on how you define manga. Short manga were being translated in Tokyo Puck at the beginning of the 20th Century, and even in Maru Maru Chinbun at the end of the 19th Century."

Post a Comment